This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

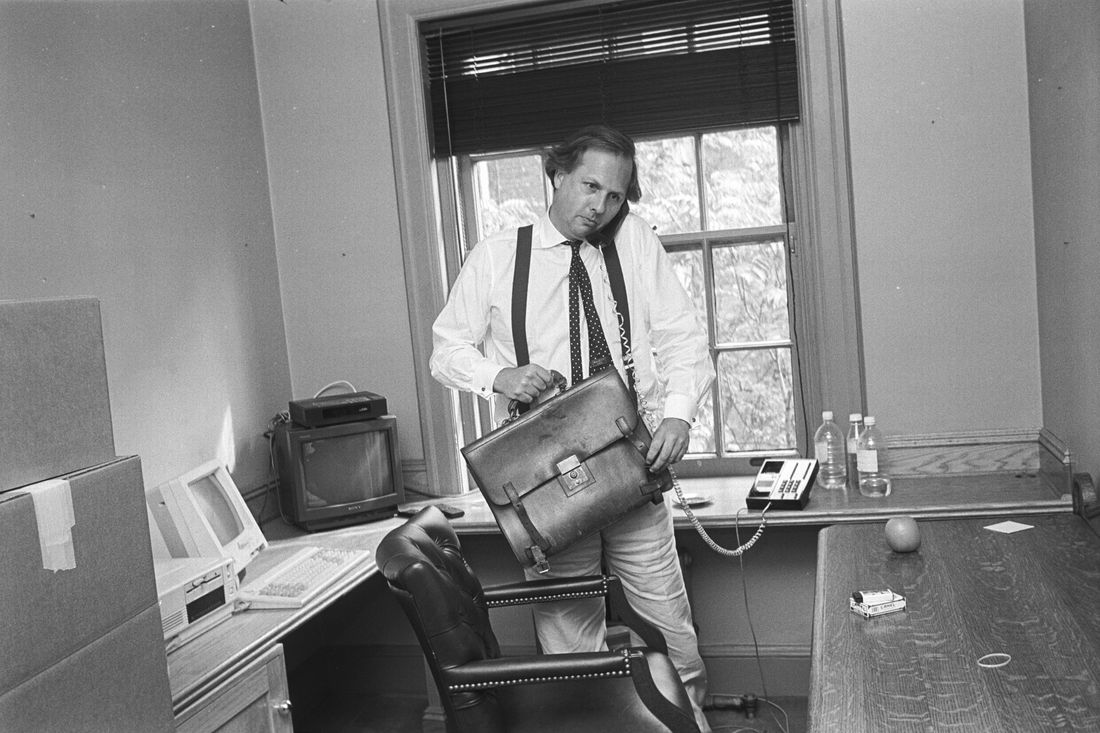

In 1991, I was named the editor of the New York Observer, a desperately sleepy Upper East Side weekly broadsheet that I hoped to turn into a must-read. About a half-year in, the paper was where I wanted it to be, it was getting noticed, and so I started sending a couple of dozen complimentary copies to friends, many of them editors in Britain and Europe. I didn’t know this at the time, but Si Newhouse, the head of Condé Nast, would take a twice-yearly tour of all his international properties, with stops in Milan, Paris, and London. He was on one of these trips in early 1992, and, as he told me later, everywhere he stopped, he would see copies of the Observer in his editors’ in-baskets. Si returned to New York under the misguided impression that the paper was a huge international hit — that everybody was reading it. About three months later, he called me and asked if I would like to get together for a coffee after work. I said of course. This was a Thursday. The meeting was set for Monday.

I fretted all weekend about how I was going to handle whatever he was going to say or offer. Like just about everyone else in New York’s various publishing industries, I was dying to be a part of Si’s glittering literary empire. On the Monday, I hopped in a cab and headed over to Si’s apartment at U.N. Plaza. We settled in a long window seat that overlooked the East River.

Si got right down to it.

He said, “I have two magazines, and I wonder if you’d be interested in either one of them.” I braced myself. “Vanity Fair and The New Yorker.”

My heart skipped a beat, and I could feel the dryness on my lips. I swallowed. At Spy, the magazine I had co-founded before going to the Observer, we’d made an industry out of making fun of Vanity Fair, relentlessly — the writers, the editor, the content, everything. It was constant and withering. But I had read The New Yorker since I was a kid. I explained my very awkward history with Vanity Fair and its staff and contributors.

Si just said, “Well, I guess it’s The New Yorker then.” I felt weak and had trouble speaking.

About two weeks after the fateful meeting with Si, one of his assistants called me and said that they were going to be announcing the change in two days’ time. The morning of the announcement, Anna Wintour called me and said simply, “Graydon, it’s going to be the other one.”

I said, “What do you mean?”

She said, “It’s going to be Vanity Fair. Act surprised when he tells you.”

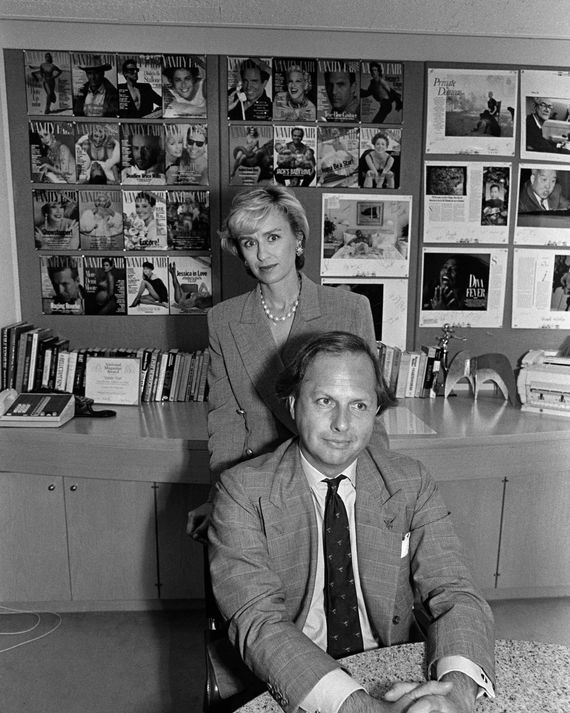

I thought, Oh fuck. I had no choice, I felt, but to accept the news. When Si called, an hour or so later, he said there was a change of plans: “It’s going to be Vanity Fair. Are you okay with that?” I said, “Yes, of course, absolutely.” I put the phone down and began to worry. Behind the scenes, what had happened, clearly, was that Tina Brown, then at Vanity Fair, had, at the last moment, insisted on moving to The New Yorker, and Si had agreed. I couldn’t really fault either of them in this decision.

Two weeks after leaving the Observer, I turned up at the Condé Nast Building on Madison for my first day of work. Joining me was Aimée Bell, who had been with me at Spy and had followed me to the Observer. Tina Brown hadn’t yet vacated her office on Vanity Fair’s floor, so we were assigned to a sort of holding pen on the executive floor that had been vacated by Dick Shortway, the former publisher of Vogue. In the afternoon of that first day, I met with the senior staff in the magazine’s conference room, where Si introduced me. To say that the collective mood was funereal would be putting a rosy tint on it. New editors generally mean changes, and changes can mean unemployment. When the new editor has spent the past half-decade ridiculing the magazine, its senior staff, its contributors, and its house style of overoxygenated writing, well, that does nothing to lighten the mood. I would have hated me if I were in their place.

I was already getting word that the staff was in revolt. As were the advertisers. The publisher, Ron Galotti, made no secret of his feeling that he had drawn a weak hand. Almost immediately, there were rumors — in print and out of it — that I was going to be fired. And I hadn’t even put out an issue.

Shortway’s office was not large, and meetings with outside writers and editors on staff at Vanity Fair often resembled the stateroom scene in the Marx Brothers’ A Night at the Opera. When I at last moved down to the editor’s office on the Vanity Fair floor, I encountered what I recall was a riot of burgundy and teal. On the walls outside, where the assistants sat — the job came with two! — Tina Brown had hung framed newspaper and magazine articles that had been written about her. All had been carted off to her new digs at The New Yorker, save for one. I didn’t want to be seen removing it. This would be a “Page Six” item waiting to happen. Aimée had an idea: “Let’s ask to have the wall painted.” The next day, painters arrived and removed the last remnant of Tina Brown’s wall of fame.

I would get to the office at five or 5:30 in the morning to read and edit. I was under terrible pressure. The industry was ridiculing me. The New York Establishment, so long coddled by Vanity Fair, was in something of a panic. The atmosphere was so poisonous I wouldn’t even bring my family into the office. A handful of the Tina Brown allies who had been left behind were deeply hostile and subversive. Readers were horrified by my editorial decisions — or so I was told by the holdover staff.

In those early days and months, pretty much everything went wrong. With a big magazine, you have to constantly feed the beast. For Vanity Fair, with anywhere between 120 and 150 editorial pages to fill each month, you have to assign a properly significant story (3,000-to-15,000 words) every three days in order to survive. Stories often took months to report and write. Then a month to edit, fact-check, and lay out. Then weeks to print and distribute. Figuring out stories that were both topical and of interest months down the line was the key to success. When I arrived at Vanity Fair, there was almost nothing lying around that I thought was worth publishing. There was a wonderful dispatch — about Russia, as I recall — by David Remnick, which mysteriously had not run, but by that point it was out of date. I cobbled together the fall 1992 issues as best I could. It would take me the better part of a year to get to the point where issues were able to be built around stories that I wanted rather than ones I could lay my hands on.

I was constantly worried that I was going to lose my job. The only encouragement I got was from Si. An editor is only as good as the support of his or her proprietor. And in this respect, Si had no peers. If he ever wobbled over his decision to hire me, he never showed it.

Going from Spy and the Observer to Vanity Fair was like moving from a youth hostel to a five-star hotel. We had a receptionist in the elevator area who handled calls and directed guests to the correct offices. A lovely woman in an English maid’s uniform came to make fresh coffee every few hours. My office had an adjoining private bathroom so luxurious that when a colleague from Spy came up to visit one day, she said it looked like Mitzi Gaynor’s.

When traveling on business, I stayed at the Connaught in London, the Ritz in Paris, the Hotel du Cap in the south of France, and the Beverly Hills Hotel or the Bel-Air in Los Angeles. Suites, room service, drivers in each city. For European trips, I flew the Concorde. I took round-trip flights on it at least three times a year for almost a decade. That’s something like 60 flights. My passport picture was taken by Annie Leibovitz!

Staff members could expense their breakfasts — not a working breakfast with a writer or photographer. Just breakfast. Large dinners at home were catered. Flowers went out to contributors at an astounding rate, sometimes just for turning a story in on time. One staff member who was a holdover from the old regime would get so depressed at the mere thought of my being there that she would send flowers to herself just to perk up her spirits. On the company account, of course.

There were interest-free loans to buy houses or apartments. Even the moving costs were covered by the company. I desperately wanted a bigger place for our growing family and so we bought an apartment in the Dakota. Like so many New Yorkers, I had always been entranced by the building. It loomed large in both old New York history and the city’s contemporary culture. Much of the fascination was due to the people who had lived there — not just John and Yoko but also Leonard Bernstein, Lauren Bacall, Judy Garland, and Boris Karloff. Can you imagine being a kid there on Halloween and knocking on his door?

The architect Basil Walter came in to design the millwork and oversee the renovation. And we filled it with old pieces from our parents and French flea-market finds. At Thanksgiving, we’d take the kids up to the roof to watch the Macy’s Thanksgiving Parade. And for the first time, I had an office at home. It was small and windowless, but it was mine, all mine — away from the hectic, glorious antics of our four children. I papered the walls with 1940s ordnance-survey maps and hung from the ceiling a huge model of a DC-3 that I had bought at a flea market in Connecticut. It’s where I could think and edit and plot out the next issues.

As flush as the operation was, I knew I had to change the culture at Vanity Fair if I was to survive and perhaps thrive. Both socially and journalistically. I edited every single word that went into the magazine — and continued to do so for the next quarter-century. At the beginning, I wanted to change the voice, which mostly meant cleansing the florid baroqueness of the language. In the Vanity Fair I inherited, a restaurant wasn’t a restaurant, it was a “boîte.” A book wasn’t a book, it was a “tome.” A party wasn’t a party, it was a “fête.” People didn’t say something funny, they “chortled” or “quipped.” I issued a list of words henceforth banned from Vanity Fair copy. Out went words like abode, opine, plethora, and passed away (for “died”). Out went glitzy, coiffed, wannabe, A-list, and even celebrity. Out went chops (for “acting abilities”), donned (as in “put on”), boasted (as in “had” or “featured”), eatery (for “restaurant”), flat (for “apartment”), flick (for “movie”), fuck (okay in a quote but not with regard to the actual sex act), also honcho, hooker, schlep (as in “to lug something somewhere”), scribe (as in “writer”), and Tinseltown. All found their way into the copyedit boneyard.

I also had to make the culture less poisonous. You could feel the venom in the corridors. Changing this certainly wasn’t easy, but gradually, Aimée, Chris Garrett (who came on as my managing editor), and I tried to soften the office atmosphere. I wanted to take it from the viperish nest it had been and make it a warmer, more collaborative place. About two years in, I came to the somewhat belated conclusion that the animus came from four offices — all of which were filled with leftovers from the ancien régime.

There was Marina Schiano, the style director, or, as her masthead title had it, “creative style director,” which I always found funny. Surely style director should have implied a certain amount of creativity. She had been a muse for Yves Saint Laurent in her younger days. The men in the art department found her exotic. I had trouble getting over her bitter attitude toward just about anyone in her orbit. Marina especially couldn’t stand me, and try as I might, I couldn’t get her around to my way of thinking. She was paid upwards of $350,000 to do the styling for eight magazine covers per year. I was told by somebody on the staff that one of her duties during Tina Brown’s reign was apparently to show up at her apartment and help style her clothes for the day. I wasn’t sure whether that was true or not, but I had been dressing myself in the mornings since I moved out of shorts and had no real need for this service.

Then there was Sarah Giles, an import from London and someone the new Vanity Fair hands like Aimée and Matt Tyrnauer (another recruit from Spy and the Observer) believed was a plant, left behind to shower dinner-party mates with tales of our incompetence. Her parents were Lady Kitty Giles — a title inherited from her father, the ninth Earl De La Warr — and Frank Giles, of London Sunday Times fake “Hitler Diaries” infamy. Sarah didn’t really have a function at Vanity Fair, as far as we could tell. She had had the reputation of being an effective story fixer — although I think it might have been Sarah who told me this. To everyone’s amusement, she did have a pet rat, named Ratty. What her purpose was at that point, aside from delivering dispatches about my inadequacies around town and protecting her friends in the magazine’s pages, escaped me.

Michael Caruso was a senior editor who bristled at every edit I made to his copy. There were a number of stories in “Page Six” during this period pitting him against me, and in all of them, he came out as the white-hat savior of journalism and me as something far less than that.

And finally, there was Charles Churchward, the art director. He was certainly talented. But in the end, he struck me as the sort of person who worked better with a stiletto pinned to his neck. My brand of attempted collegiality, for lack of a better word, just never jelled with Charles. He left of his own volition and decamped to the Vogue floor, where he worked for the next decade or more.

The first three — Schiano, Giles, and Caruso — I let go all the same week. It was more people than I had fired in my life up to that point. I simply told each one of them that this wasn’t working for me and that I thought it was time for them to spread their wings elsewhere.

I said to each of them, “The trouble is you’ve confused politeness for weakness.” Caruso was in a state of disbelief.

He said, “You’ve got to be joking.”

I said, “No, not joking at all.”

I was surprised by the result of the purge. Rather than have the rest of the office in an uproar, the staff was quietly thrilled with what I had done. And despite the fact that I am, at heart, a beta male, this moved me, at least in some eyes, closer into the alpha category.

As far as the office environment went, it was like pulling open the curtains at Miss Havisham’s. Everything seemed sunnier. I may have actually developed a spring in my step. People started working with each other in a noncombative manner. Interoffice memos were being signed off with an unheard-of “Thank you.” I began to bring my kids into the office. Things had changed. Even gossip about my imminent firing began to die down after Si Newhouse personally dispelled the rumors.

One major advantage in these rocky early days was that there was no budget at all — that is to say, the budget had no ceiling. I could send anybody anywhere for as long as need be. The cost and the expenses involved were sometimes enormous. One article, about the near collapse of Lloyd’s, the London insurance market, may have been the most-expensive-per-word magazine story ever written. And we never published it.

The first person I reached out to with my new checkbook was Christopher Hitchens. I first met him in the 1980s at a party in Greenwich Village, when he was writing for The Nation and was then known mostly to the tribal left. Christopher was among the last great public intellectuals of the liberal intelligentsia, but he was one with wit and charm — which made him much more palatable to people in the middle and even to conservatives. By the time I got to Vanity Fair, he was writing for Lewis Lapham at Harper’s. I called Christopher and, with Si’s checkbook in hand, got him to sign on. Christopher and I went to Elaine’s that night to celebrate, and God if we didn’t bump into Lewis. Christopher told him that he was going to be leaving Harper’s to work at Vanity Fair. Lewis handled the news with supreme elegance. I think he realized that it would be better for Christopher to be introduced to the much wider audience Vanity Fair would offer. We sat down and had a drink. Well, many drinks.

Christopher was to write a column each month as well as articles and profiles. His well-calibrated but unflagging intake of alcohol and nicotine produced nothing but swift and faultless prose, even after lunches or dinners where others would be hors de combat. Dinner was a bacchanal of anecdote and erudition, recitations from Flashman and Wodehouse giving way to declamations from Gibbon and Homer. He was infinitely funny, better company than just about anyone. As for the writing and drinking, I remember going to lunch at La Goulue when Aimée and I were at the Observer. Christopher had a couple of Scotches before the starter, a couple glasses of wine with the main course, and then a brandy to wash things down afterward. Back at the Observer offices, we plunked him down in front of a typewriter and he banged out a review of a thousand words of near perfection in less than an hour.

Writing is a tough business — especially the sort of detailed, rigorous, longform narrative journalism that Vanity Fair came to be known for. And this reportage has its own unique set of demands. Vanity Fair writers were sent to the far corners of the earth to report. They would leave their families for weeks or months at a time and return home and on deadline had to assemble all the reporting and write a good tale — almost like a condensed book. Every one of their facts then had to be stood up by the researcher — or researchers — checking the article. And then the story had to be reviewed by the legal editor. Sometimes this process, from idea to final copy, would take three or four months. Stories that ran as long as 17,000 or 20,000 words might take even longer.

I believe that all great magazine stories must have a combination of the following elements: narrative (that is to say, a beginning, a middle, and an end), access (to the principals, or those on the immediate periphery of the principals), conflict (always a welcome addition), and disclosure (moving the scholarship on the topic at hand along — in other words, new information). You can get by with three of these necessities. But with four, you have a great chance at producing a memorable work of journalism.

An article could be killed for various reasons. Perhaps it didn’t meet expectations — although that was a rare occurrence given the caliber of writer I worked with. Perhaps in the course of closing our story another magazine published one on the same subject that was just as good — this was another reason to kill it. I had a rule that I wouldn’t break, even when the fortunes of magazines everywhere began their slide: I never paid a kill fee — a staple of the business. A kill fee meant the writer generally got about a quarter of the amount the story was assigned for if it didn’t run for one reason or another. I had been a writer in my recent, previous life, and I knew just how brutal the whole ordeal was and how most in the trade lived from assignment fee to assignment fee. Whether we ran the story or not, the writer got paid in full.

The editor’s job can be likened to that of a choirmaster. You have all these disparate voices. It’s the editor who must somehow bring these gifted soloists together in an issue to form a sort of choral harmony. Some writers — especially the ones who had been editors in the past — were terrific at coming up with their own story ideas. Others relied on me and the other editors to come up with the ideas. Marie Brenner, one of my favorites, and a master at the longform journalism we practiced, had a habit of coming in with ideas that I thought were less than inspired. On a couple of occasions, I got her off her notion by telling her that she was a home-run hitter and that even if she did a brilliant job on the story she was suggesting, it could never be more than a double. You should never step up to the plate unless a home run is a possibility, I would tell her. Marie would leave the office saying how right I was, and a day or two later we’d come up with an idea for her that would allow her to hit another home run. Marie’s body of Vanity Fair work was extraordinary. She produced one explosive story after another, many of which were turned into films, including Michael Mann’s 1999 film, The Insider, and Clint Eastwood’s 2019 film, Richard Jewell. Writers like Marie, Sebastian Junger, Michael Lewis, Maureen Orth, and Bryan Burrough, all of whom crafted journalism like novelists, became vital parts of the Vanity Fair stable. The masthead just grew and grew. Very few people left the magazine whom we didn’t want to leave.

Dominick Dunne was a significant element of the franchise that I inherited and was, for a long time, a huge asset to the magazine. He could be prickly — especially to the younger staff, which I was not fine with. But we needed him and, to a great extent, he needed Vanity Fair. The magazine’s readers devoured his dispatches from the 1993 trial of the Menendez brothers. He would soon become perhaps the most famous print journalist in the world for his monthly and knowing coverage of the O. J. Simpson courtroom circus.

Vanity Fair writers like Nick were paid like no other writers. He was well on his way to earning half a million dollars a year, plus generous expenses and months of free and continuous accommodation at the Chateau Marmont or the Beverly Hills Hotel during the trials he covered for us: not just the Menendez brothers and O. J. Simpson but, later, the music impresario Phil Spector, who shot a young actress, Lana Clarkson. We treated our stable of writers like the stars they were. This meant assigning them to diligent, talented editors and dispatching flowers or bottles of Scotch at regular intervals. I bought Nick the same Christmas gift every year: a dozen square, dark-blue Smythson notebooks with his name embossed on the covers. Each one had about 200 light-blue pages. These books became a hallmark of his during the O. J. trial as he made his copious notes. Nick had filled them all by the end of the trial, and I had to give him his next Christmas batch early that year.

Newsstand sales were a monthly measure of a magazine’s success in those days. When the numbers were good, they kept Si’s lieutenants off my back. I cared about the quality more than the sales, and above all, I wanted readers to read. It was the covers, though, that sold the magazine. For the subjects of those covers, movie stars were for the most part the lingua franca of the global newsstand.

Jane Sarkin, Vanity Fair’s features editor, was our Hollywood and show-business conduit. She booked — wrangled, as they say — pretty much every cover. She also, along with Krista Smith, our West Coast editor, organized the photo portfolios embedded in our “Hollywood” issues. Jane cultivated and dined with agents and publicists. She described herself — when she was interviewed about one of her covers — as a very ordinary girl from New Jersey. But Jane wasn’t ordinary; she was exceptional. She had started as a receptionist at Andy Warhol’s Interview magazine and rose, she would say, because while she was working, most of the rest of the staff was in the basement doing coke and having sex. Jane loved the world of movie stars and celebrities, and they trusted her.

Jane had exceptional stamina as a celebrity handler and ego-tamer — skills that came in useful when keeping agents, publicists, and overbearing managers at bay. She also kept them away from me, for which I will be eternally grateful. In addition to all of this, she served as Annie Leibovitz’s full-time in-house connection. What I appreciated about Jane was that despite the operatic drama surrounding her job, she never ever came to me with a problem, only with a solution.

Among her gets was the first picture, taken by Annie, of Tom Cruise and Katie Holmes’s baby, Suri. It’s hard to imagine now that this was a great national obsession. But in the spring of 2006, it was. Because the couple hadn’t wanted publicity for their newborn child, rumors and conspiracy theories built to a fever pitch: They hadn’t actually had a baby; they had, but it had been taken away by the Scientologists; or, alternatively, there was a baby, but it wasn’t Katie’s. In 2006, Cruise was the biggest star in the world, and the search for Suri was Jane’s big truffle hunt. She had worked on many covers with Cruise, and, after a while, she got the exclusive. He invited Jane and Annie to Telluride, where they spent a week doing the story on Suri in great secrecy. Jane wrote the cover article herself. We were so concerned about a leak that we sent Annie’s pictures to the printers chained to the wrist of a security guard. The pictures were stolen anyway by someone at the plant who tried to peddle them to the papers. We found the person and shut that operation down. With a fair amount of padding, we managed to somehow spread the Cruise “family album” over 22 pages. Looking back at it now, I honestly find it difficult to understand what all the fuss was about.

From When the Going Was Good: An Editor’s Adventures During the Last Golden Age of Magazines, by Graydon Carter (Penguin Press).